Between 1338 and 1339, the Sienese magistracy of the Nove (citizens chosen to administer the city) commissioned Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1290–1348) to paint the walls of the Sala della Pace in the Palazzo Pubblico, where government meetings were held. The result is a monumental cycle of frescoes, for a long time titled La Pace e la guerra but now known as L’allegoria del buon governo. It depicts the metaphor of just versus unjust government and their respective effects on the city and countryside: a remarkable political painting that has much to say, both symbolically and historically. Let’s take a closer look.

The Sala della Pace in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico

To enter the Sala della Pace, you must first leave behind the so-called Sala del Mappamondo, named for the lost Mappamondo created in 1345 by Lorenzetti himself. You then enter through a 15th century door along the east side, while the original entrance, now closed, was on the north wall. This north wall, extending the full width of the room, hosts the Allegoria del Buon Governo and begins the narrative cycle. To the right, you’ll find the Effetti del Buon Governo on the City and Countryside, while on the opposite side, on a single wall, are depicted the Allegoria and the Effetti del Mal Governo.

The message is conveyed not only through the images but also via words: inscriptions and scrolls appear within the scenes and around the lower border, helping the viewer understand their meaning. This practice was very common in Sienese political painting; a masterful example is the wonderful Maestà by Simone Martini in the already-mentioned Sala del Mappamondo. But what does Lorenzetti’s masterpiece represent, and what does it mean?

The Allegoria del Buon Governo

To grasp the iconographic program of the Buon Governo, we should start with the wall showing the Allegoria del Buon Governo. At the top, Sapientia supports a large set of scales beneath which the crowned figure of Giustizia stands out prominently. On either side of the scales, two angels bustle about, administering justitia distributiva (on the left, decapitating one man and crowning another) and comutativa (on the right, handing measuring tools to two merchants).

Two cords then descend from these angels, twisting into a single rope in the hands of Concordia, seated just below. The rope is passed hand to hand among twenty-four worthy men before it reaches the bearded figure on the throne, the Comune di Siena or Bene Comune, dressed in the city’s colors. Below him is the city’s symbol: the wolf nursing the twins, referring to Siena’s legendary connection to Rome. Next to the Comune, the three theological virtues, Fides, Charitas, and Spes, hover while at his feet we see knights and defeated enemies (in the foreground, two lords can be seen handing over a castle).

All around, seated, are the four cardinal virtues: Fortitudo, Prudentia, Temperantia, and Iustitia, together with Magnanimitas and Pax, perhaps the most famous character of the cycle. Clad in white and reclining slightly, Pax gazes serenely toward the adjacent wall, where the Effetti del Buon Governo unfold.

Along the lower border of the frame is the artist’s signature, and in the space beneath it, an inscription praising justice and its power to unify citizens:

“This holy virtue, wherever it governs,

leads many souls to unity,

so that these, gathered together,

make the common good their lord;

which, to rule its state, elects

never to take its eyes away

from their resplendent faces,

the virtues surrounding it.

Because of this, they willingly render

tithes, tributes, and authority over lands,

and so, with no wars,

every civic endeavor is ensured –

both useful and pleasurable.”

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The Effetti del Buon Governo

The narrative continues with a flowing inscription that urges those “who govern” (the Nove) to follow Justice, “the virtue that shines brighter than any other”, as it ensures harmony and balance.

The same ideals appear in the representation of the Effetti del Buon Governo, one of the pinnacles of medieval topographical painting.

Within the city walls – daringly shown in perspective – of an ideal city resembling Siena (the Duomo and bell tower in the distance on the left are unmistakable), activities abound: a man goes to the cobbler, while another heads to a food shop; between them, a group of students listens to a teacher’s lesson. On the other side, a small wedding procession is watched by three onlookers from a balcony, while in the neighboring building a cat strolls along a railing. The city is beautiful (notice, for instance, the rooftop loggia decorated in red and yellow) and bustling, even with building work: slightly higher up, some laborers construct a palace, and in the center, a group of women (or jesters) dances, symbolizing harmony. A sense of serenity and peace pervades the entire painting, stretching beyond the walls: in the countryside, a tranquil atmosphere defines various agricultural activities, from cultivating olives and grapes to working the rolling hills in the distance.

High above, Sapienza soars, once again urging adherence to Justice for the Bene Comune through her scroll.

The refined and meticulous pictorial treatment reveals the influence of Giotto and Simone Martini, and also suggests that Lorenzetti may have been aware of northern miniature calendars. Added to this is his remarkable ability to reproduce natural details in a precise, evocative way.

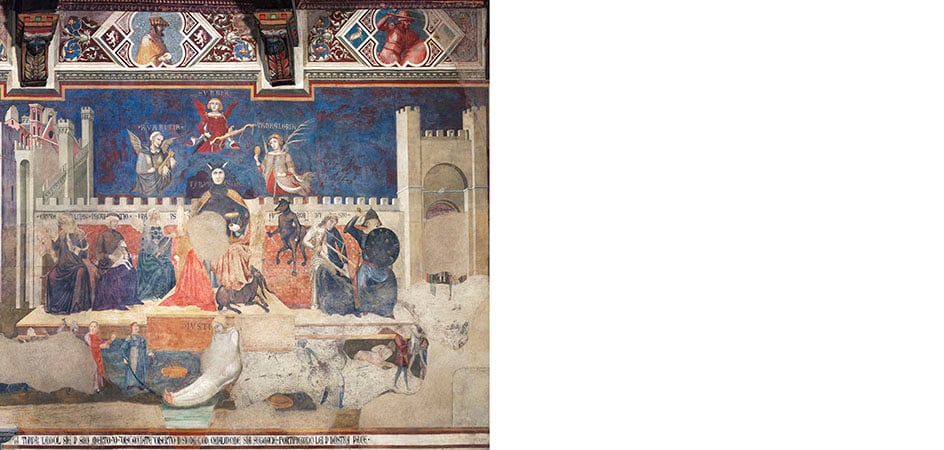

The Allegoria e gli Effetti del Mal Governo

Opposite this scene, the west wall depicts both the causes and effects of the Cattivo Governo. Unfortunately, the fresco is damaged, and much of the painting is lost. Yet we can still make out Giustizia in chains (or “bound,” as the inscription recalls, referring to the rope in the first fresco), surmounted by Tirannia, a figure with diabolical features. Surrounding her are the Vices: Avaritia, Superbia, and Vanagloria above, and Crudelitas, Proditio, Fraus, Furor, Divisio, and Guerrabelow. It is a monstrous assembly, completed by the dreadful Timor, who looms over the countryside, sowing terror and agony. Within the city, the situation is no better: death, robbery, and destruction await those who fail to uphold Justice.

There are three inscriptions – mirroring those of the other fresco – reinforcing the message with unequivocal words, such as:

“For the sake of their own gain, in this land

justice is subjugated by tyranny,

thus along this path

no one passes without fear of death,

for outside they plunder and within the gates as well”.

The patronage and the choice of theme

As mentioned, the Nove commissioned the work to Lorenzetti – a project of extraordinary complexity, rich in symbols and allegories. We do not know for sure who planned the theme and composition, but it is plausible that Lorenzetti himself – described by Lorenzo Ghiberti as a learned and ingenious man, and by Vasari¹ as a philosopher and gentleman – was actively involved in developing the subject, likely drawing from Aristotelian doctrine.

What is certain is that it responded to an immediate political need in Siena at the time: promoting to both rulers and the general populace the benefits stemming from civic virtues, as opposed to the disastrous consequences of tyranny.

In the late 1330s, Siena – long troubled by internal strife among its noble families – also felt the threat of potential social upheaval. Around its borders, powerful aristocratic dynasties were taking over once-free city-states, and Siena itself had been eyed for conquest, though it had so far escaped. In this uncertain and fearful climate, Lorenzetti’s fresco warns citizens about the outcomes that a different order might bring, vividly illustrating the pros and cons of one form of government over the other.

The power of Lorenzetti’s painting lies in its dual approach: the evocative realm of allegorical figures and symbols, and the realistic portrayal of Siena’s architecture and heraldry.

Both metaphorical and credible, the Allegoria del Buon Governo carries a uniquely persuasive force, conveying universal ideas that remain strikingly relevant today.

Currently, the Sala della Pace is closed for restoration, but – as soon as it’s possible – make sure not to miss the chance to visit the Museo Civico and see in person the most famous political fresco of the Middle Ages in all its renewed splendor.

1 Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574), an artist, architect, and man of letters at the Medici court, also wrote Le vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri (published in 1550 and again in 1568 with additions), a foundational work for Italian art historiography.