Symbolic, realistic, evocative: over the centuries, landscapes have taken on different meanings depending on the historical period, artistic movement, and each artist’s interpretation. Here, we will retrace its evolution by looking at some of the most significant milestones, from its early days right up to the threshold of Impressionism.

Early landscape painting: 14th and 15th centuries

Although it became established as an independent genre only in the 17th century, the landscape – understood broadly as both natural and urban settings – appeared in painting much earlier. We can already find it, for instance, in the works of Giotto (c. 1265–1337), who pioneered a quest for realism that would influence Western art for centuries. Along with a focus on psychological depth, Giotto paid particular attention to natural elements, depicting them with unprecedented realism not just for decoration but also for narrative purposes. A clear example is the fresco San Francesco che dona il mantello al povero (1295–1300) in the Basilica Superiore of Assisi, where the hills in the background outline a tangible space that converges right at the figure of the saint, the focal point of the scene.

Equally allegorical yet no less realistic is the setting painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1290–1348) in his fresco cycle Effetti del buono e del cattivo governo in città e in campagna (1337–1339), located in the Sala dei Nove of the Palazzo Pubblico di Siena. Here, rural life and urban activities unfold within a 14th century setting, portrayed in meticulous detail.

Almost a century later, Masaccio (1401–1428) introduced a groundbreaking innovation to painting: linear perspective. In works like Il Tributo (c. 1425, Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, Cappella Brancacci), an austere backdrop constructed along mathematical principles amplifies the overall realism of the biblical scene with its monumental mountains, leafless trees, and a wind-rippled lake.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), meanwhile, looked to Flemish painters and the revolutionary artistry of the Low Countries, studying and portraying natural phenomena. From rock and cloud formations to waves and the growth of plants, Leonardo was fascinated by all aspects of nature. In his attempt to replicate them in his paintings, he adopted one of the most innovative techniques in art history: lo sfumato. His landscapes – such as the one in the Vergine delle rocce (1483–1490, Paris, Musée du Louvre) – capture the essence of human vision by blending forms and using light to create a setting that feels vibrant and tangible. The use of light would become a key feature of 16th century painting, especially in Northern and Venetian art.

The 16th century: between symbolism and spectacle

Admired by artists such as Albrecht Dürer, Joachim Patinir (c. 1485–1524) worked in Antwerp, specializing in biblical scenes set in unusual landscapes: often viewed from a bird’s-eye perspective, his sweeping vistas occupy most of the canvas, making human figures appear almost incidental. Patinir also introduced a specific lighting element – fire – into Italian painting. Tiziano (1485/1490–1576) drew on Patinir’s influence in his Orfeo ed Euridice (1508, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo). The myth is told in two scenes: on the left, Euridice is bitten by a dragon (rather than the usual snake), while on the right, Orfeo, having emerged from the Underworld, turns to look at her, losing her forever. The entrance to Ade glows from within with the light of a flame. Dynamic, shifting, and expansive, the landscape is built through contrasting color masses and becomes the work’s true protagonist, heightening the tragedy of the story.

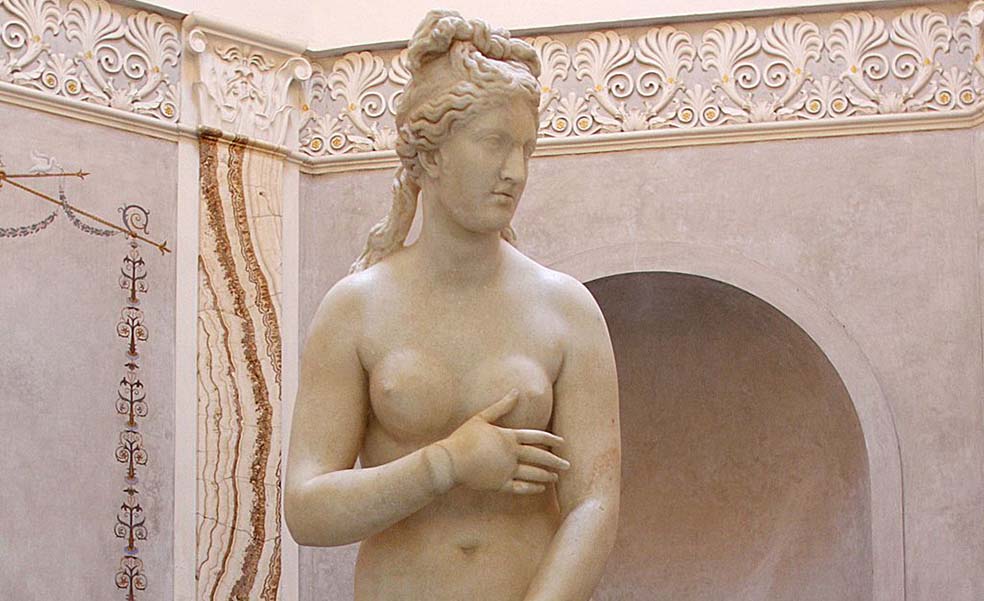

Grand, spectacular, and theatrical – befitting the Mannerist style – best describes Paolo Caliari, known as il Veronese (1528–1588), in his cycle of frescoes at Villa Barbaro in Maser (Treviso), around 1560. The painted trompe-l’oeil architecture and landscape illusions combine keen naturalism with a vivid personal imagination to create an Arcadian idyll rooted in a long tradition. Everything signals the coming affirmation of landscape painting as its own genre.

The 17th century: classicism and idealization

In the 17th century, with the rise of specialized art workshops, landscape was no longer just a metaphorical backdrop to sacred or secular themes; it became a subject in its own right. Leading the way at this time was the Accademia bolognese dei Carracci, and its classicist vision of art. During Annibale Carracci’s (1560–1609) Roman period, he painted the lunette Fuga in Egitto (c. 1603, Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphilj) for the chapel in Palazzo Aldobrandini. The emotional thrust of the scene is conveyed through an extraordinarily balanced composition, where the grandeur of the landscape harmonizes perfectly with the figures.

This idealized, purer-than-life portrayal of nature also characterizes the work of French painters Nicolas Poussin(1594–1665) and Claude Lorrain (1600–1682). Their landscapes are modern yet simultaneously mythical, bathed in a luminous, tranquil atmosphere that remains largely separate from the foreground narrative. For instance, in the Paesaggio con Orfeo e Euridice by Poussin (1649, Paris, Louvre) – a reinterpretation of the same story that Tiziano had once treated so differently – the drama becomes an occasion for a measured, serene representation, where even the presence of Castel Sant’Angelo in the background fits perfectly into the overall composition.

At the opposite end of the spectrum from these French painters, Rembrandt (1606–1669) had a very different approach, especially regarding the depiction of light. No longer diffuse and uniform, his light sources are pinpointed, so masterfully directed that they can unsettle the viewer. The Paesaggio con ponte di pietra (1636–1637, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum) is a case in point: light coming from the right illuminates the tree foliage, briefly brightening the scene. Meanwhile, the dark sky, the countryside, the modest stone bridge, and the figures on the river remain in a penumbra charged with tension.

These varied 17th century artistic experiments paved the way for a wide range of subgenres – marinescapes, architectural views, cityscapes, winter scenes, and rustic landscapes – that artists would continue to develop throughout the 18th century, fueled by studies of optics and an increasing interest in theatrical stage design.

18th century landscape painting

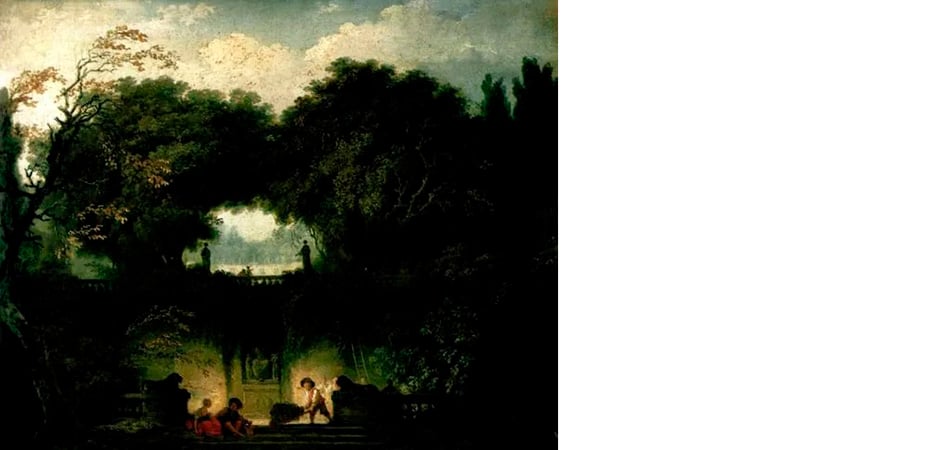

Theatrical style is evident in the works of Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), who initiated a new and highly successful subgenre known as fêtes galantes: elegant gatherings set amid lush nature, often featuring classical elements like statues and monuments. The strolling noble couples, shown conversing flirtatiously, are not situated in a carefree, festive atmosphere so much as in idyllic, timeless settings that subtly evoke the fleetingness of pleasure.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) also followed in this vein. In 1756, he set off on a Grand Tour¹ that took him to Rome, Naples, and Venice, experiences that inspired his early landscapes – such as The Giardino di Villa d’Este (c. 1760, London, Wallace Collection). Clearly echoing Watteau’s compositions, Fragonard’s figures are gently lit in majestic yet secluded gardens populated by statues of gods and amorini. However, unlike his predecessor, Fragonard moved away from the melancholic sense of transience, wholeheartedly embracing the lighthearted, playful spirit that would characterize his subsequent works, culminating in the nearly erotic scenes of his mature period.

A third name worth mentioning in any brief overview of 18th century landscape painting is Canaletto, the alias of Giovanni Antonio Canal (1697–1768). The son of Bernardo, a theater painter, he inherited his father’s knack for perspective and stage design, blending them with remarkable skill in his views of Venice. These were greatly admired by English travelers and brought him widespread acclaim, leading to commissions by the British consul Joseph Smith, who purchased dozens of Canaletto’s works – later acquired by King George III of England. The Bucintoro di ritorno al molo il giorno dell’Ascensione (1730–1735, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection) is among them and showcases the painter’s ability to combine everyday life details (in this case, a traditional Venetian ceremony) with a monumental urban setting heightened by atmospheric effects and multiple vantage points.

From the romantic era to the Macchiaioli: the 19th century

The late 18th century to the mid-19th century was marked by Romanticism, a diverse movement that took hold in Germany and England before spreading across Europe. Emphasizing a return to an authentic past, interiority, subjectivity, and the quest for the sublime, Romantic artists made landscape painting a privileged medium for exploring fantastical and picturesque themes, giving ample scope to personal emotion.

The shifting skies and scenes of John Constable (1776–1837) reflect the artist’s inner feelings: though he aspired to scientific accuracy, his work such as La cattedrale di Salisbury vista dalla residenza del vescovo (1823, London, Victoria and Albert Museum) conveys a profoundly intimate, personal vision.

For Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), the landscape became a realm for the sublime aspect of Romanticism. His paintings capture not only his emotional state but also the era’s fascination with the unknown, the fantastical, and the infinite. Pioggia, vapore e velocità (1844, London, National Gallery) exemplifies this, depicting the atmospheric effects of a storm on a locomotive and the surrounding environment in a haunting, evocative way that merges machine and nature.

It is impossible to remain unmoved by the Viandante sul mare di nebbia (1818, Hamburg, Hamburger Kunsthalle) by the German painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), often hailed as the manifesto of Romantic landscape painting. As in his other works, the solitary figure is shown from behind, standing on a rocky summit and gazing at a mist-shrouded, cold, and melancholic landscape deeply imbued with spirituality and symbolism. It is a canvas that still inspires a profound, contemplative response.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The 19th century was a time of great social change and extraordinary intellectual ferment, leading to new trends that challenged Romantic notions. One such movement was the Barbizon School, which arose in the 1830s in the forest village of Fontainebleau, France. Founded by painters like Théodore Rousseau (1812–1867), who bridged Romanticism and Realism, this school rejected academic conventions and sought to portray nature realistically, thus renewing the landscape tradition.

It also anticipated the en plein air approach of the Impressionists and influenced the revolutionary experience of the Macchiaioli, a movement that emerged in pre-unification Tuscany in the 1860s in opposition to the artistic norms of the time.

The Macchiaioli were particularly devoted to landscapes, especially Tuscan countryside scenes. They juxtaposed blocks of color and light – “macchie,” or patches – to achieve striking compositional unity reminiscent of 15th century painting.

Though there are many notable figures and famous works from this group, a prime example is Giovanni Fattori(1825–1908) with his Maremma toscana (1877–1880, Florence, Palazzo Pitti). In addition to illustrating the artist’s interest in rural themes, this painting encapsulates the Macchiaioli’s signature elements: a predominantly horizontal, almost photographic framing, strong contrasts of color, and at times an extreme simplification of forms.

With the emergence of Impressionism and later Avant-Garde movements, the landscape genre moved away from shared styles, becoming ever more subject to the individual visions of each artist. This evolution confirms the versatility of the genre – an inexhaustible source of inspiration and admiration, both then and now.

¹ The Grand Tour was an educational journey across Europe, particularly popular from the 16th to the 19th centuries, undertaken by young aristocrats to refine their knowledge and expand their intellectual horizons. While the trip length varied, Italy was considered a must-see destination.