Located in the monumental complex of the Dominican convent, the Museo di San Marco houses the largest collection of works by Beato Angelico, who lived and worked here for many years.

But that’s just one reason to visit.Inside, you’ll also find masterpieces by Fra Bartolomeo, Paolo Uccello, and Domenico Ghirlandaio, among others. Meanwhile, the building itself – designed by Michelozzo – epitomizes the formal and spatial harmony typical of early Renaissance architecture. A treasure trove awaits. Here’s what to see at the Museo di San Marco in Florence

The cloister of Sant’Antonino

The convent of San Marco underwent major restoration at the behest of Cosimo de’ Medici, who entrusted it to Michelozzo in 1439. Michelozzo was a prime representative of the architectural style of the period.

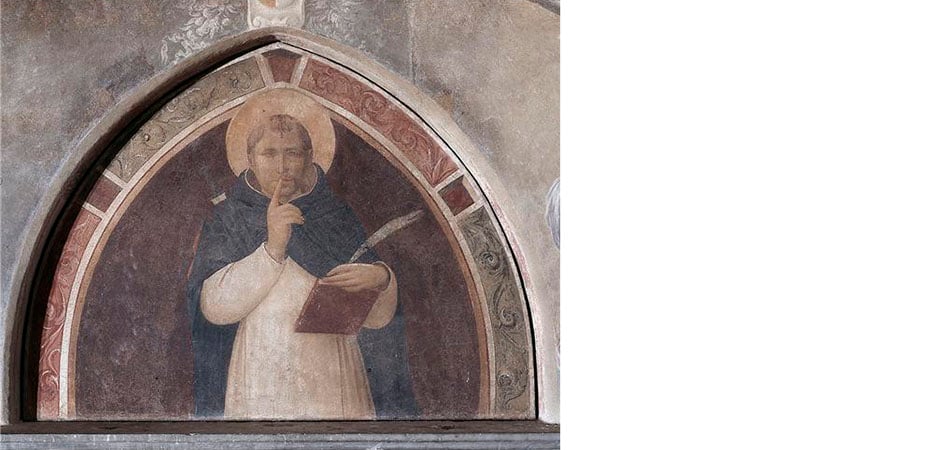

The Cloister of Sant’Antonino is the first of two cloisters designed by Michelozzo (the second, larger one is dedicated to Saint Dominic and reserved for the friars who still inhabit part of the original complex, so it’s not open to the public). Four corridors with vaulted ceilings supported by elegant Ionic columns welcome visitors after they enter from the austere vestibule. Open and harmonious, the Cloister invites contemplation and sets the spiritual tone of the convent. The lunettes feature frescoes from different periods and by different hands; among the most significant are those painted by Beato Angelico that herald the various rooms once used by the religious community. For instance, above the door to the still-active church, his San Pietro Martire (c. 1442) calls for silence with the familiar gesture of pressing his index finger to his lips.

Beato Angelico is also responsible for the large fresco of San Domenico in adorazione del Crocifisso (1440–1442) on the back wall of the west side. A subject with strong mystical overtones, it appears in several of the artist’s San Marco paintings. Although the setting is austere, rather than flattening the figures, it actually makes them stand out: the Angelico captures both the saint’s deeply absorbed expression and Christ’s lifeless body with great care.

The Sala Capitolare and the bell

Opening onto the Cloister is the Sala Capitolare, where the Dominican friars once gathered – its original purpose emphasized by Beato Angelico’s 1442 fresco of San Domenico che tiene in mano la regola e nell’altra la disciplina, an unmistakable reference to the administration of justice.

Housed here is a 15th century bell famously known as the “Piagnona”, nicknamed for its dramatic history. Cast in a Florentine workshop (likely on commission from Cosimo de’ Medici), it originally hung in the bell tower of San Marco. On April 6, 1498, while Girolamo Savonarola¹ was besieged in San Marco by Medici supporters, the bell was rung all day long, calling the people of Florence to defend the friar. Its long, desperate sound earned it that sorrowful nickname.

After Savonarola’s execution the following May, the bell also faced punishment: removed from the tower and thrown to the ground – sustaining severe damage – it was then dragged through the city streets, whipped, and ultimately exiled to the bell tower of San Salvatore al Monte. It would return to San Marco only years later.

The Pinacoteca and Beato Angelico’s panel paintings

From the Cloister of Sant’Antonino, you can also enter the Sala dell’Ospizio, named after its original function before it was converted into a gallery. Here, you’ll find the Pinacoteca, which boasts the highest concentration of Beato Angelico’s panel paintings. This collection was formed alongside the secularization of the convent, specifically to gather and document Dominican artistic heritage. Many of these paintings come from various Florentine churches and nearby areas following the 19th century suppression of religious orders.

Among Beato Angelico’s most famous works here, four merit special mention:

The altarpiece of the Deposizione

Initially entrusted to Lorenzo Monaco for the Cappella Strozzi in the chiesa di Santa Trinita in Florence, the altarpiece’s pinnacles (featuring the Noli me tangere, Resurrezione di Cristo e Pie donne al Sepolcro) and predella (depicting the lives of Santi Onofrio e Nicola, now at the Galleria dell’Accademia) were completed by Monaco before his death. Beato Angelico took over about ten years later, in 1435, painting the central scene and the saints in the side panels. He captures the moment of Christ’s descent from the Cross, with Maria and the other women praying on the left and a group of men on the right. Among them, you can spot one of the Strozzi patrons in the young man at the far right wearing a red turban, while the figure in dark headgear next to Christ is said to be a portrait of Michelozzo.

Although the turreted city in the background and the overall monumentality of the figures still evoke a Gothic influence, the keen psychological insight and measured emotion in the faces and gestures clearly reflect the new Renaissance sensibility.

The Annalena altarpiece

Named for the convent of San Vincenzo di Annalena, where it once stood (though it may not have been its original destination), it’s thought to have been painted between 1434 and 1438. This makes it the oldest Renaissance altarpiece – a distinction it shares with being the first “Sacra Conversazione” of the humanist era, as evidenced by the novel semicircular arrangement of saints around the throne. The continuous background, which creates a unified space rather than segmenting it, was also groundbreaking for its time.

The Tabernacolo dei Linaioli

Commissioned in 1433 by Florence’s powerful linen-weavers guild for their headquarters, it features Santi Marco and Pietro on its outer panels and scenes from the saints’ lives plus the Adorazione dei Magi in the predellas. Inside, Beato Angelico painted San Giovanni Battista e San Giovanni Evangelista (on the doors) flanking the central image of the Madonna col Bambino surrounded by angels. Again, you can see a blend of medieval tradition in the iconographic scheme and new Renaissance ideals in the clearly defined, Masaccio-inspired spatial construction. Measuring 260×330 cm, the tabernacle also boasts a marble frame designed by Lorenzo Ghiberti (and executed by his pupils), further enhancing its grandeur.

The Giudizio universale

Painted between 1432 and 1435 for the chiesa di Santa Maria degli Angeli, likely positioned above the officiant’s seat, this altarpiece is complex in design. Beato Angelico tackles the sacred theme in a novel way: the scene is centered on a row of open tombs stretching toward the horizon’s vanishing point and guiding the eye to the blue sky and the figure of Christ, who symbolically connects its two “wings.” On the left is Paradise, with the blessed joyfully dancing in a circle; on the right is Hell, where the damned are tormented and devoured by monstrous devils.

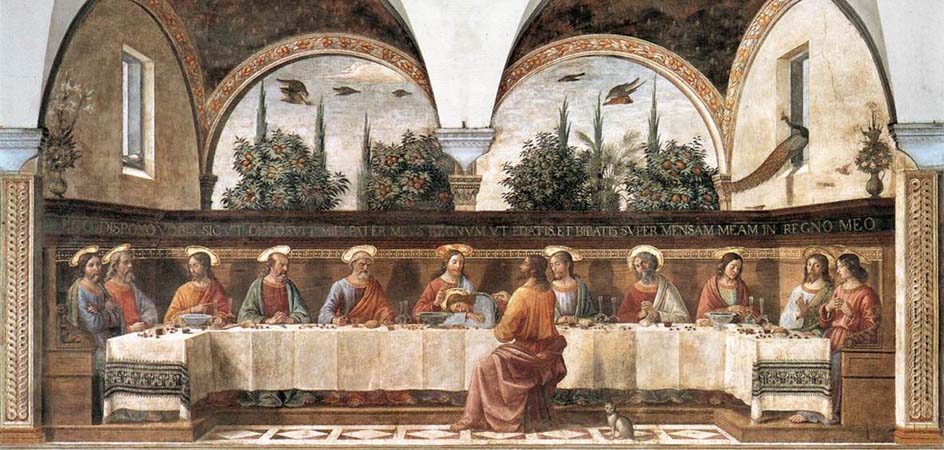

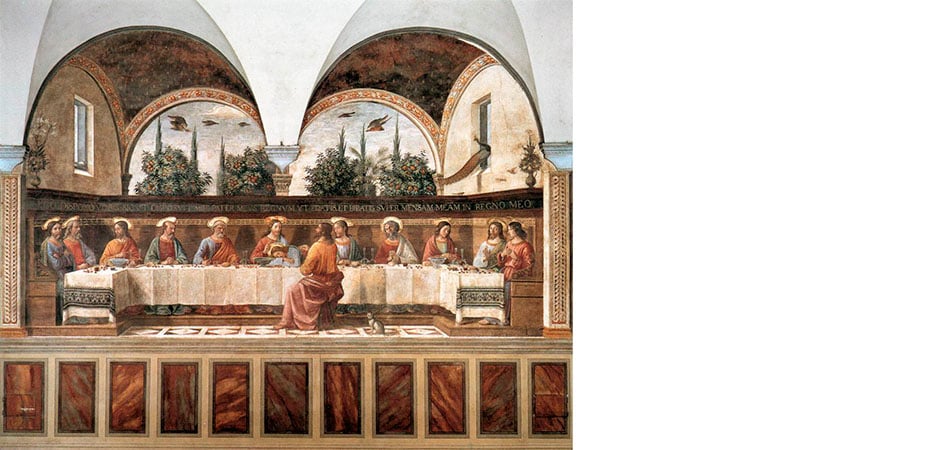

The Refettorio piccolo and the Cenacolo by Ghirlandaio

In the Refettorio piccolo – so named because it served a smaller, more select group than the main dining hall for friars and pilgrims – don’t miss Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Cenacolo. In the late 15th century, the Ultima Cena was being chosen more and more often (replacing the more common Crocifissione) to decorate refectories.

Ghirlandaio’s fresco stands out for its perspective, which creates an illusion of extended space, for the soft illumination from the left, and especially for its wealth of realistic and symbolic details. The artist was known for capturing the tastes of his contemporaries in paint, evident in the ornate tablecloth and the tableware. Meanwhile, the animals and vegetation allude to Christian themes: lilies and roses symbolize purity and martyrdom (as does the palm), the peacock represents the Resurrection, and the cat is associated with the devil.

The Upper floor: the Annunciazione by Beato Angelico and the Ritratto di Savonarola by Frà Bartolomeo

On the upper floor, you’ll find the grand cycle of frescoes Beato Angelico created for the convent. Sealed off for the cloistered friars’ use, it remained unknown to scholars and hidden from the public for a long time.

As you climb the stairs, you are greeted by Beato Angelico’s famous Annunciazione (c. 1440). One of the artist’s best-known works, it captivates with its elegance, balance, and mysticism. The encounter between the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary is imbued with spiritual purity through a pared-down composition, gentle light, and soft colors – hallmarks of Angelico’s style at San Marco. This intimate, contemplative quality becomes even more pronounced within the monastic cells, where Fra Angelico and his assistants painted sacred themes and biblical events.

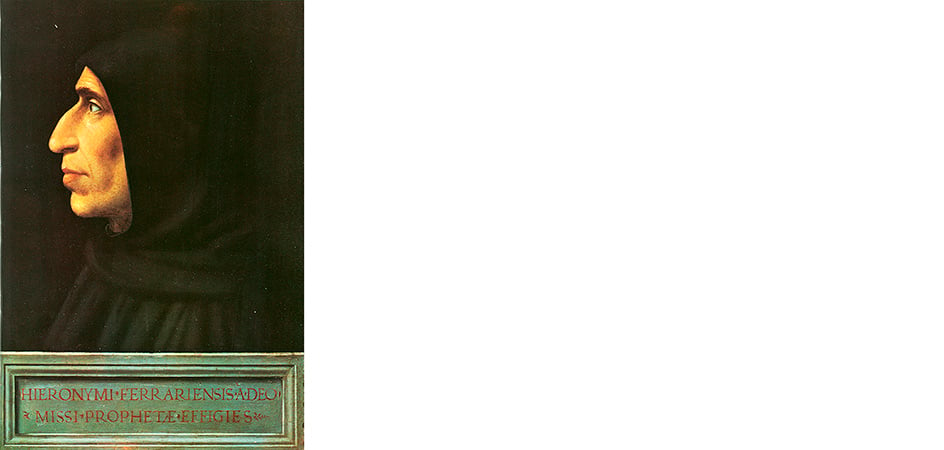

Almost all of the 43 cells lining three sides of the Sant’Antonino Cloister are adorned with frescoes by the friar-painter or his workshop, with the exception of three at the far end of the second corridor. Initially used as the Vesteria del Giovanato, these rooms were taken over in 1484 by Girolamo Savonarola, who lived there until his arrest in 1498. Today, they hold relics and objects connected to the friar, including the Ritratto di Frà Girolamo Savonarola (1490–1498) by Fra Bartolomeo, an artist-monk who was a close follower of the preacher from Ferrara. In his portrait, Savonarola is shown in profile with a pronounced nose, tightly closed lips, and a focused gaze. The background merges into the friar’s black hood, a choice emphasizing the painting’s introspective character.

If this brief guide to the Museo di San Marco in Florence has piqued your interest, there’s only one thing left to do: buy your tickets and see it all in person. It’s an experience not to be missed!

1 Girolamo Savonarola (b. 1452 in Ferrara) was a Dominican friar, preacher, and political figure, active primarily in Florence. A fervent advocate for deep reform within the Church, he was eventually hanged and burned at the stake for heresy in the Tuscan city.