The human body has always captivated artists, and depictions of nudity can be found as far back as antiquity. Yet their meaning shifts with evolving tastes, sensibilities, and social values. To better understand this progression, we have chosen five artworks where the nude plays a leading role – sometimes even boldly so – revealing the aesthetic and cultural standards of their time.

The nude in Greek and Roman art

For the Greeks of the 5th century, nudity was either a divine prerogative – therefore inviolable – or male, primarily associated with physical exercise. Gymnasia, the ancient training grounds, were where young men worked out entirely unclothed (the word’s root is the same as gymnos, meaning naked in Greek). Artistic representations from this era conform to social conventions that linked physical beauty with moral virtue, viewing bodily perfection as a symbol of youth, strength, and integrity. This ideal is evident in the monumental kouroi and korai: statues with fixed, idealized iconographic postures.

Over time, these sculptural forms became more relaxed. Bodies took on softer poses, appearing to “move” in space yet remaining governed by precise compositional principles such as symmetry, harmonious proportions, and balance. This is the essence of classical art produced by celebrated artists like Polyclitus and Phidias.

This cohesive, nearly divine vision of beauty began to crumble with the Macedonian conquests and Alessandro Magno’s dominion. From then on, nudity increasingly became a source of aesthetic delight in its own right, no longer limited to representations of higher moral qualities. Not coincidentally, the female form also became an object of artistic focus and admiration.

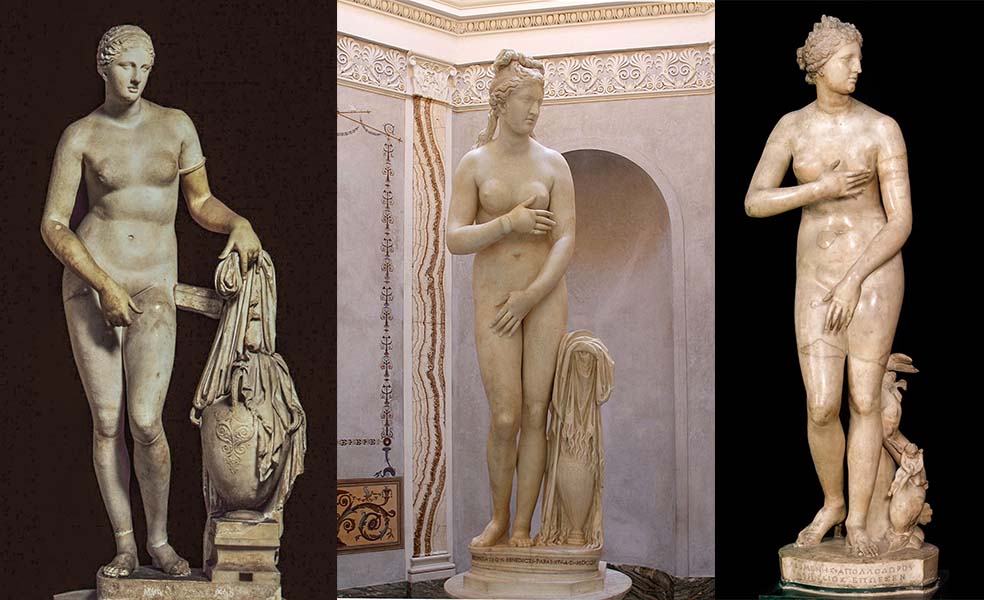

The Afrodite cnidia and the Laocoonte

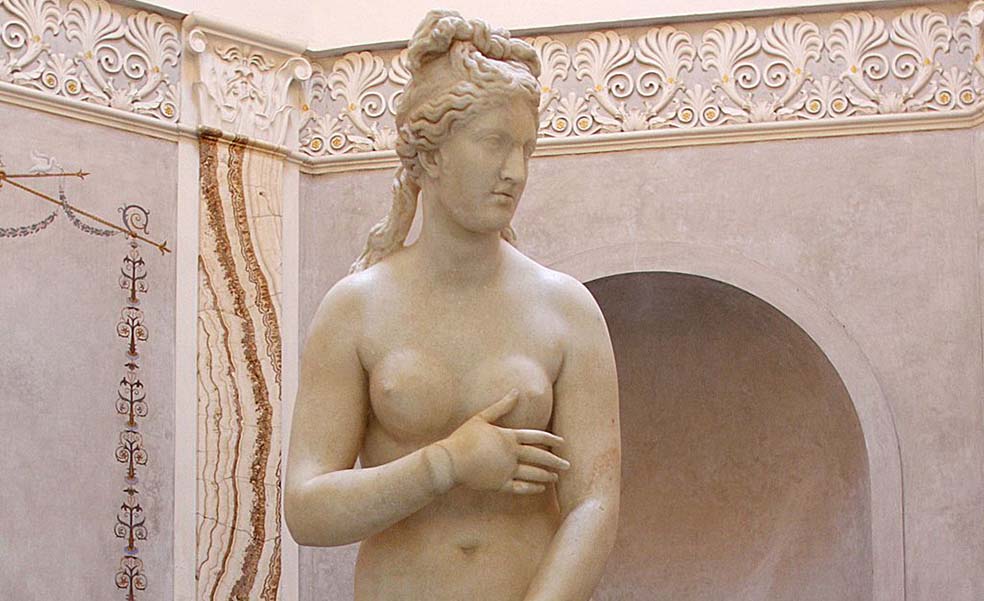

The Afrodite cnidia of Knidos – now lost but known through subsequent copies – illustrates this gradual shift in perception. In the surviving replicas, the goddess is about to enter the water. With her left hand, she removes her robe, while her right hand covers her pubic area – an action that already hints at an onlooker’s gaze. The sculpture’s novel sinuosity and almost painterly softness of form did not go unnoticed by contemporaries. In his Naturalis Historia, Plinio recounts: “It is said that a man, seized with lust for the statue, hid himself overnight, united himself with the statue, and left a stain as proof of his desire”.

The popularity of this sculpture gave rise to a compositional model known as the Venere pudica, and several versions survive, such as the Venere capitolina (a Roman copy of a Greek original from the 2nd century BCE, found in the Musei Capitolini in Rome) and the Venere de’ Medici (2nd century BCE – 1st century CE, housed at the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, briefly replaced in the Napoleonic era by Antonio Canova’s Venere Italica created between 1804 and 1812 and now back at the Uffizi).

These pieces attest to the arrival of the Hellenistic spirit, characterized by the fully humanized portrayal of art – exposing the body and its emotions in a striking and relatable way, whether in its more sensual forms, such as the aforementioned Veneri, or in dramatic ones, epitomized by the renowned Laocoonte (1st century BCE, in the Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano).The anguished nudes, caught in the deadly coils of sea serpents, convey raw terror and suffering in what became the most celebrated ancient sculptural group of the Renaissance.

The Middle Ages and the early renaissance

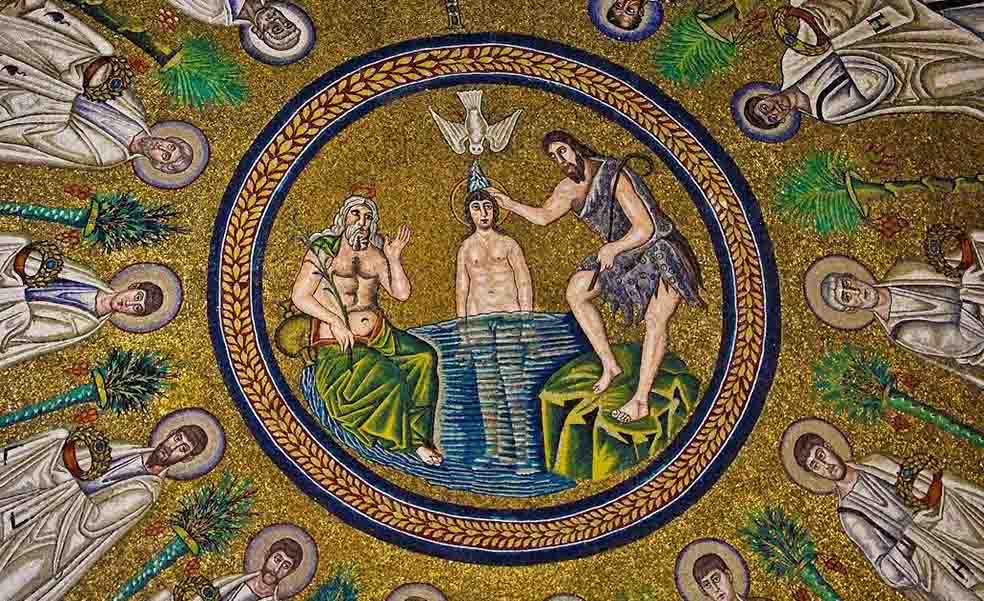

With the spread of Christianity from the 5th century CE onward, nudity took on a symbolic, non-sexual meaning connected to morality and doctrinal teachings. Adamo and Eva were nude – shamelessly so before their sin – and Cristo appears naked in depictions of the Baptism (even before the Crucifixion), as seen in the mosaics of the Battistero degli Ariani in Ravenna.

Their bodies, however, are rendered in a schematic, simplified manner, far from the naturalism of classical art – something that would not resurface until Nicola and Giovanni Pisano, Arnolfo di Cambio, Pietro Cavallini, and Giotto.

Gothic art likewise adhered to a sparse anatomical geometry – leaving no room for visual temptation – whether depicting Eden, the Passione di Cristo, or the Giudizio Universale.

Nevertheless, change was on the horizon. Artists and scholars were about to rediscover Greek and Roman art, as they returned repeatedly to ancient masterpieces and their long-forgotten harmony of forms rejected by medieval Christianity.

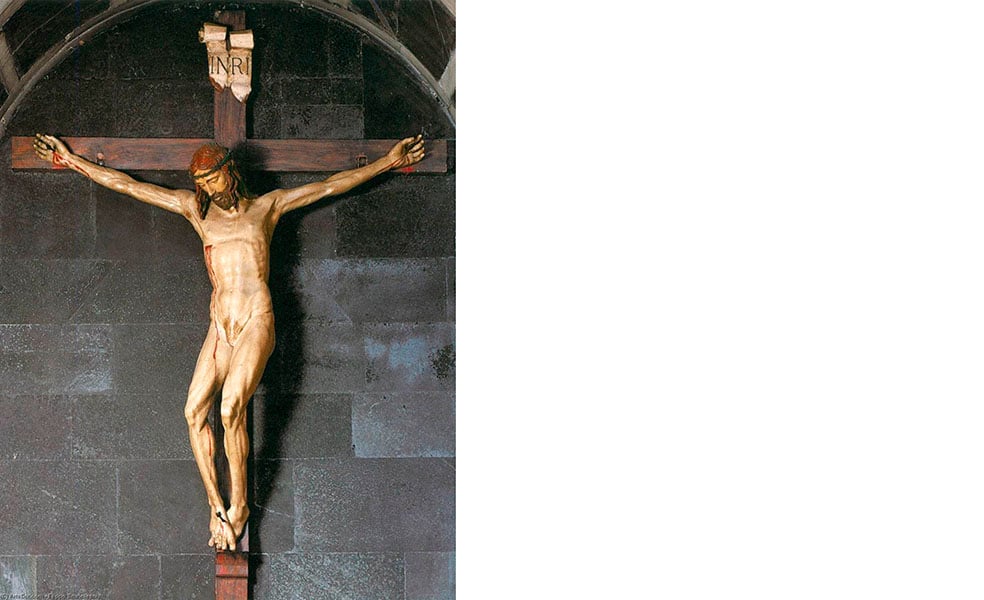

While Brunelleschi set the trend with his Crocifisso (ca. 1410–1415, Santa Maria Novella, Florence), portraying Christ nude on the Cross, it was his friend Donatello who set another milestone in the history of the nude in art.

The David by Donatello

Completed around 1440 and now housed at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence, the David by Donatello reflects the renewed interest in the fluidity typical of Hellenic art, its grace, and its balance. Emphasizing beauty more than might, it is the first nude bronze of the Renaissance, depicting the biblical hero as a beardless youth, elegant and composed in his triumph over the giant Golia. The enemy’s head lies at David’s feet, though he appears almost indifferent, frozen in a perfect contrapposto pose directly inspired by ancient models that the artist studied during his stay in Rome.

According to Vasari,¹ Donatello’s curiosity was not limited to classical influences. In Vite, Vasari writes: “…he understood the depiction of the nude in a more modern way than any other artist before him, and he dissected many corpses to observe their anatomy beneath the skin.”

Indeed, combining real-life observation with the imitation of antiquity became a topic of conversation and debate among the intellectuals of the time. Alongside biblical subjects, mythological ones emerged in equal measure, moving seamlessly between the stories of saints and those – often steeped in symbolism – of ancient gods and heroes. In both, the nude is openly observed and celebrated.

The High Renaissance

During the 16th century, the human body, its forms, and proportions became a true field of study for artists and scholars alike, from Leonardo da Vinci to Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo. In this era, painters and sculptors drew on classical art, but they reinterpreted and transcended it, propelled by personal struggles, theological debates, and social contradictions.

The David by Michelangelo

Michelangelo is perhaps the 16th century artist who most developed a personal interpretation of the nude. His nudes were certainly influenced by antiquity – he greatly admired the Laocoonte mentioned earlier – but also imbued with tangible passion and extraordinary expressiveness. We see this clearly in the 1499 Pietà (San Pietro, Rome), where the dead Christ is depicted in a disjointed, believable posture.

We see it again in David (1501, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence). The tension of the impending action emerges in the sculpture’s well-defined, flexed musculature – idealized yet fundamentally human. The David by Michelangelo is heroic even before the fight begins: his gaze is fixed on the enemy, his body caught in a graceful yet taut stance, a massive block of marble that throbs with mortal emotion.

These works prefigure the monumental achievements Michelangelo would later accomplish in the frescoes of the Cappella Sistina.

The Venere by Tiziano

Both a place of vice and devotion, Venice in the 16th century stood out as one of the liveliest cultural, artistic, and social hubs in Italy. Here, mythological subjects provided the perfect excuse to depict sensual bodies – ideal for portraying eroticism.

Amid this context of thinly veiled pruderie, we cannot ignore the Venere by Tiziano Urbino (ca. 1538, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence). Whether goddess, bride, or simply “la donna ignuda” (as her patron, Guidobaldo della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, called her), she openly engages the viewer while covering her pubic area with her left hand – directing attention precisely there. The erotic power of the painting was such that it continued to cause scandal well into the 19th century. During his visit to the Uffizi, Mark Twain described it as “…against the wall, without so much as a leaf or a rag upon her … the foulest, the vilest, the most obscene painting the world possesses – the Venere by Tiziano … . It was painted for a bagnio [brothel], and it was refused because it was a trifle too strong”.

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

Regardless of judgments on the work’s perceived immodesty, it is clear that 16th century Italian art was increasingly free from rigid iconographic constraints and now expressed itself – nudity included – simply for the pleasure of doing so.

The pinnacle of this attitude is Il ratto delle Sabine by Giambologna (1582, Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence): a sculptural group born purely out of artistic intention, without a specific commission or theme, to which a subject was only assigned after its completion.

Yet soon enough, things would change again. The spirit of the Counter-Reformation, with its restrictions and iconoclastic fervor, spread throughout Italy. Nudity in sacred art was concealed (Daniele Ricciarelli, nicknamed “Il Braghettone,” famously covered parts of Michelangelo’s works), and a few decades later, it was formally prohibited.

Still, despite these and other later attempts at suppression, the nude would never disappear entirely but would continue to evolve. It remains with us to this day, reinterpreted and attuned to current tastes and sensibilities, as evidenced by the works of Yves Klein, Vanessa Beecroft, and David LaChapelle.

1 Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) was an artist, architect, and scholar at the Medici court, as well as the author of Le vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri (published in 1550 and again in 1568 with additions) – a foundational text for Italian art historiography.