The Annunciation is one of the most recurring themes in Christian art: since the 6th century, painters and sculptors alike have tackled the portrayal of this sacred scene, each in their own distinct way. In this article, we’d like to recall a few examples produced between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance that, thanks to their qualities or the innovations they introduced, stand out from all the others.

What is the Annunciation about?

The main account of the Annunciation comes from the Vangelo of Luca, which tells of the visit of the Archangel Gabriele to Maria, “a virgin betrothed to a man of the house of Davide, named Giuseppe.” Gabriele brings a message: Maria will conceive the Son of God, immaculately, give birth to Him, and name Him Gesù. He “shall reign over the house of Giacobbe forever, and of His kingdom there shall be no end.”

Maria accepts the Archangel’s words and humbly embraces the will of the Lord. Giuseppe does the same, after receiving a dream in which an angel announces the same events to him.

While the written description seems fairly straightforward, depicting it visually is not as simple. Artists must imagine various details: the setting of the Annunciation (open air, indoors, or semi-open?), Maria’s activity at the moment the Archangel arrives, their poses and distance from one another, the presence of the Holy Spirit, and so on.

In addition to these purely pictorial questions, there is another, no less important: the symbolic meaning. The Annunciation involves the Christian mystery of the Incarnation and marks the beginning of Christianity, that is, the promise of redemption after Original Sin.

But how to portray such a meaningful moment, which is so sparsely detailed in the Evangelists’ accounts?

Are you interested in articles like this?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive updates and insights from BeCulture!

The representation of the Annunciation

Many different solutions have emerged. In many depictions, Maria is shown reading sacred texts – symbolic of her devotion – or spinning thread, an activity alluding to her patient and accommodating nature.

In most representations, there is also a third figure, the dove of the Holy Spirit, sometimes replaced by the image of God the Father.

Beyond these recurring themes, each individual work has its own distinctive characteristics, influenced by the place and time it was created, and by the artist’s personal choices. Let’s take a look at a few examples together.

The Annunciazione by Simone Martini

Signed and dated (1333), the altarpiece by Simone Martini and his colleague/brother-in-law Lippo Memmi is now housed in the Galleria degli Uffizi, enchanting thousands of viewers every year. Martini chooses to capture a precise moment in the Annunciation: Gabriele has just arrived, his cloak – rendered with the flowing lines typical of Gothic art – still billowing in the air. Maria, seated on a decorated stool, closes the book she was reading and wraps herself shyly in her sumptuous midnight-blue cloak.

Between them, at the top, is the dove surrounded by angels and, on the marble floor, a vase of lilies, symbolizing the purity of the Virgin and the Son of God. Completing the altarpiece are the martyr Ansano on the left and a female martyr (still unidentified) on the right; while in the upper lunettes, we see Geremia, Ezechiele, Isaia, and Daniele.

It’s a triumph of gold: the background, the ornate frame, the halos – even the Archangel’s greeting to Maria, written in gold on gold (“AVE GRATIA PLENA DOMINUS TECUM”). It is one of the most refined examples of Gothic art: Martini, with his remarkable mastery of color and line, conveys both the human dimension of the scene – the reserved gesture of Maria – and its lofty spiritual significance.

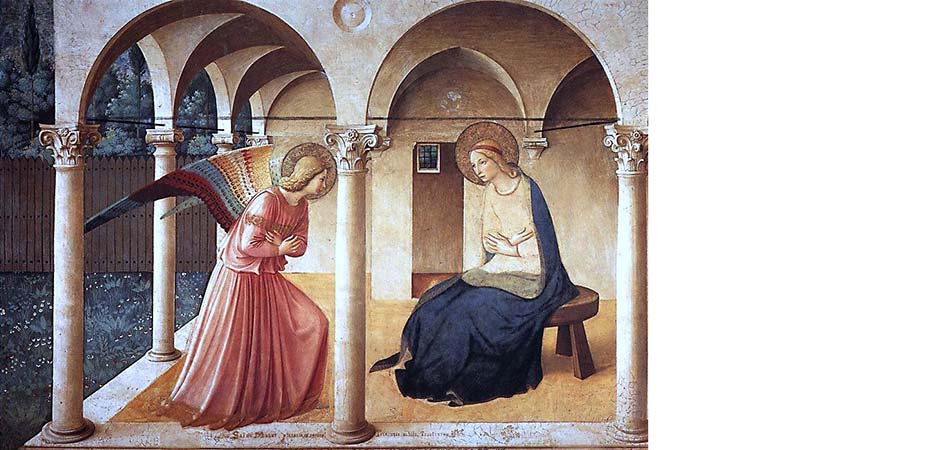

The Annunciazione by Beato Angelico

Speaking of spirituality, perhaps no other 15th century artist captured it in painting quite like Frà Giovanni da Fiesole, known as Beato Angelico. The Annunciation is one of his most frequent subjects, and the fresco in the corridor of the Museo San Marco is certainly among his finest. Before that, in the early 1430s, Angelico painted the Annunciazione now housed in the Museo Diocesano of Cortona, considered by many to be his first masterpiece.

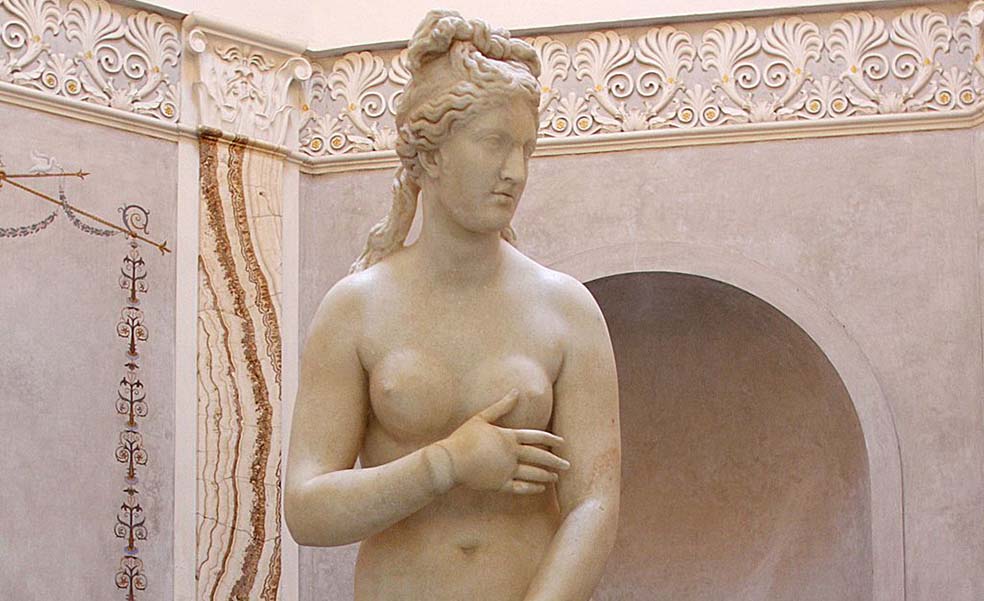

Set in a Renaissance loggia, the painting depicts the dialogue between the Archangel and the Virgin.

Gabriele addresses Maria: “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you” (in Latin in the artwork), speaking in an almost imperative tone – he raises both index fingers, one pointed at her and the other at the dove of the Holy Spirit.

Maria replies: “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word”.

What makes it special are Maria’s golden words: not only are they upside-down (implying they are meant to be read from Heaven, not Earth), but part of them is hidden behind the column, obscuring a crucial part of the text: “fiat mihi secundum” (“I am the servant of the Lord”). This is how Angelico resolves the representation of the mystery of the Immaculate Conception: by partially concealing the exact point where it is referenced.

In the roundel above the column stands the prophet Isaia, while at the back, in the garden to the left, we see the Cacciata dal Paradiso, with the Progenitors curiously dressed in contemporary clothing as they are escorted out. It’s a powerful parallel between sin and redemption.

The Annunciazione by Filippino Lippi

If Simone Martini and Beato Angelico both employ, in the cited examples, a direct dialogue conveyed by a sort of “speech bubble”, Beato Angelico and Filippino Lippi share something else: perspective. Lippi draws inspiration directly from the friar-painter and takes his solutions even further.

Just look at his Annunciazione (1483-1484) for the Sala delle Udienze del Palazzo Comunale in San Gimignano, now housed in the Musei Civici of the city. It consists of two round paintings: one depicting the Angelo annunciante and the other the Vergine annunciata. Both are organized around a clear central perspective; if we traced their vanishing lines, we would discover they intersect precisely where the viewer stands – in the space between the two paintings. This means whoever looks at it participates not only emotionally but also almost physically in the scene.

It is a scene both divided and united – by the perspective effect and by the identical painted flooring shared by the two panels. The empty space between the roundels fulfills the same function as Angelico’s column: it serves to conceal and at the same time indicate the Christian mystery, invisible to the eye (and therefore unrepresentable) yet present.

Lippi was fascinated by Flemish painting, especially Hugo van der Goes’s Trittico Portinari (1473-1478, housed in the Uffizi, Florence), which was on display in Florence at the time. Accordingly, following a typically Northern approach, he includes numerous household furnishings and everyday objects charged with symbolic meaning. The column you see behind Gabriele, without a base or capital, is closely connected to the mechanical clock behind the Virgin. Both point to time: eternal time, without beginning or end, and earthly time.

In between, once again, the mystery of the Incarnation takes place.

The Annunciazione by Lorenzo Lotto

As mentioned earlier, one of the dilemmas artists faced was deciding which specific moment of the Annunciation to paint. From the Renaissance onward, many drew inspiration from a 15th century sermon that enumerated five states of mind in Maria. The first was conturbatio, or disquiet. Over time, this state was rendered in increasingly realistic, less stereotypical ways.

Leonardo da Vinci – who studied human behavior and natural phenomena closely – had already criticized Botticelli’s Annunciazione for its excessive theatricality (“[…] an angel, whose manner of announcing looked as if he wanted to chase Our Lady out of her chamber with movements that showed as much malice as one could possibly do to a most worthless enemy, and Our Lady looked as if in desperation she wanted to throw herself out of a window […]” he wrote in his Trattato della Pittura).

Among the finest interpreters of a truly human sense of Maria’s anxiety was Lorenzo Lotto, who, in the first half of the 16th century, painted the Annunciazione now held in the Museo Civico of Villa Colloredo in Recanati.

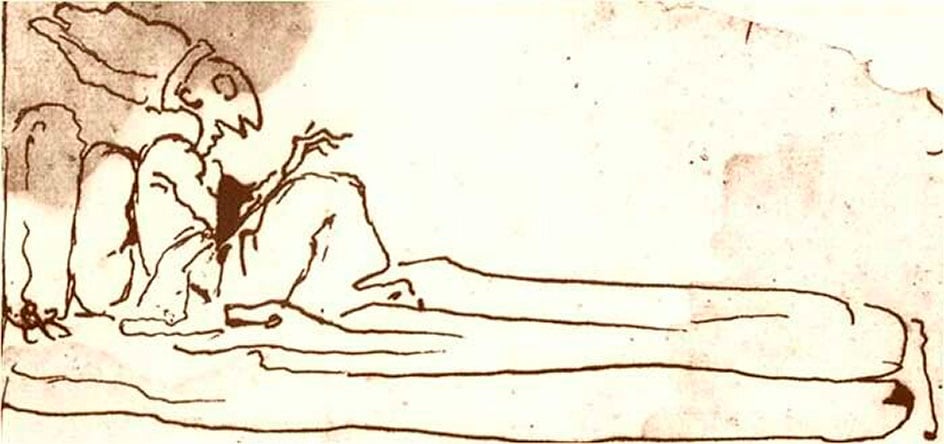

This is one of the artist’s most famous works and one of the most modern Annunciations in art history. The first novelty is the spatial arrangement of the figures, with the Virgin on the left and Gabriele on the right.

In a simple, modest interior (we can make out a canopy bed, a lectern, a shelf with books and candles, a nightcap and other garments hanging up), Maria is taken by surprise while reading. Her alarm is such that she turns her back on the divine apparition and looks at the viewer with reverential fear.

The Archangel, kneeling, with his robe still stirred by his sudden arrival, gestures upward, where God the Father seems to almost dive into the scene. He holds three lilies, symbolizing Maria’s virginity before, during, and after childbirth.

The commotion is so great that even the household cat, startled by the Archangel’s sudden entry, appears in the middle of the room, arching its back in fright. It’s an original choice, both for the subject matter and for the symbolism commonly associated with this animal (often linked to evil). Here, however, the cat’s presence makes the event feel even more domestic and believable, adding yet another touch of realism.

This journey through some of the most fascinating Annunciations of the Middle Ages and Renaissance not only highlights the unique features of each piece but also reveals how varied art’s depiction of the same story can be over time. Tracing the evolution of a subject through different eras and styles is a journey that unveils unexpected connections and new perspectives, making art history a continually alive and inexhaustible realm to explore.